Board Game Playtesting

We test our board game designs to make sure the games works like we think it does and to improve it little by little over time.

In this article we'll talk about what playtesting looks like at each stage, where to find testers, what to ask them, and how to collect feedback.

The Progression

Designs go through multiple testing phases: solotesting, guided testing, specific tests, unguided playtesting, and finally public testing.

Solotesting

Starting out, it is best to test your game by yourself to see if it works. Set up your game and assume the roles of all the players as you progress through the decisions of each player.

Congrats, you tested it yourself.

While you'll have to learn to outsmart yourself, this method shows you whether your game functions enough on a basic level to involve testers.

Guided Testing

From there you can move to teaching people how to play your game. You don't need to have a rulebook written out yet, simply set it out and explain how it works. Begin first with how to set up the game and how to win, then proceed to how the rounds or turns flow. Your goal in this phase is to get a fresh perspective on your mechanics, and to see what emotions and goals your players build around their play session.

Here's my favorite video capturing the feeling of explaining a board game.

Specific Testing

Perhaps guided testing has shown that the game is fun except around specific edge cases. Maybe you're worried that a player can't reasonably win if they are behind by a certain amount of points. Maybe testing is showing that the green deck beats the red deck 9 times out of 10.

I run specific tests to explore the rough parts of my game in order to find out possible and probable fixes. That may mean starting a test with a behind several points, or perhaps with testing out different variations of the red and green decks.

Unguided or "Blind" Playtesting

You've shown your game to be mechanically solid, but so far you've still helped your tested along the way. Now it's time to write a rulebook. In a blind playtest, you provide your testers your game and rulebook and give them no further guidance. It's imperative to not answer any questions your testers may have while playing, as that's the job of your components and rulebook. Watching your testers learn your game helps you identify where things don't make sense.

These kinds of tests can be the most frustrating, as players will do things "wrong" right in front of you while you are unable to help them have fun.

Public Testing

So far, your testers have been the people you know. These people, in general, want you to do well and assume you will eventually succeed at your goals. This allows them to provide context rich feedback. This also hurts their ability to be objective, as no one wants to be the guy who says your design is terrible.

That's why its important to get feedback from strangers who have no idea that you specifically made the game. Strangers don't care about whether your goals are met or whether your game drops off the face of the earth when they're done with it.

Imagine secretly adding your board game to a pile of random board games at a board game meetup. It's singled out to be the one played, some people hate it and loudly say as much, and some others love it, splitting off to play a rematch. Now you know what people really think when they don't stand to lose anything from voicing their opinion.

What to Bring to a Playtest

When testing in person, you can use a printed version of your game. When testing online, you can use computer programs like Tabletop Simulator or Tabletopia.

Where to Test your Game?

I like to playtest my games at board game themed bars. But you can also test your designs at Unpub events at conventions, or at local board game design clubs. I found my local design club on Meetup. There are a number of online testing communities, my favorite is the Break My Game discord. They have rulebook feedback and daily question channels and several public testing sessions a week.

What to Ask Your Playtesters

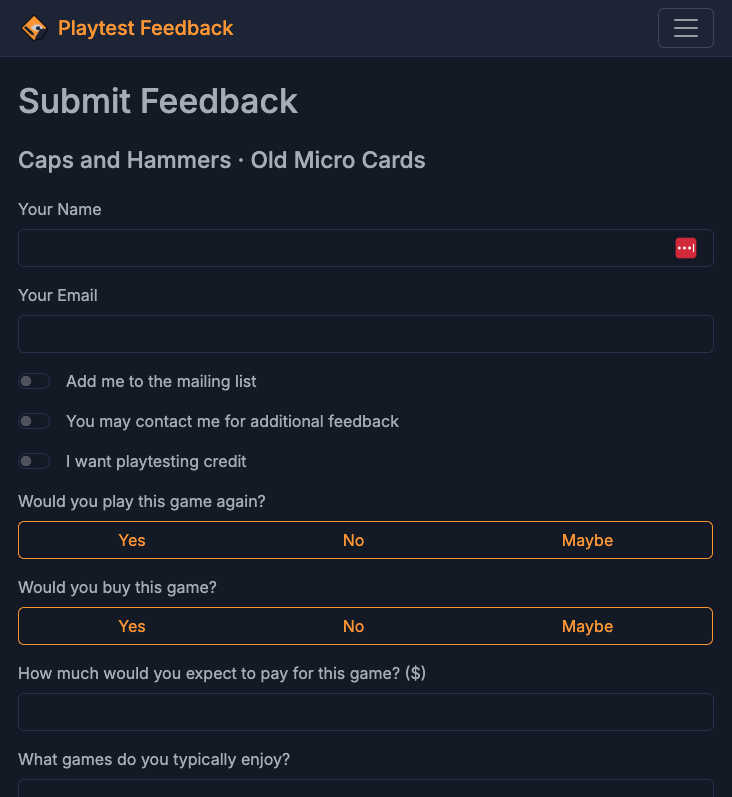

When someone tests your game, you should ask them many questions. You want to know if they would play again, if they would buy it, and how much they would pay. You also want to know what games they like, what they enjoyed most, and what was hard to understand.

It's important to ask what they thought of the rules, game length, the amount of downtime. Ask how much they enjoyed the decisions they got to make if the game feels too random or too set in stone.

Keep track of where and when you tested. Write down how long it took to play. Take pictures during the game. Write notes about what happened and what you need to fix. When the playtest is over, debrief your testers and gather all of the above feedback.

Keeping Track of Feedback

The Board Game Design has a playtest form you can print to collect feedback.

Personally, I hate taking written feedback. People write so slopely. I once thought a person's email included a Greek Psi Ψ character (it was a 4).

To avoid the written feedback I created the free mobile website www.PlaytestFeedback.com.

No errors were made in the relaying of this feedback.

Once you create a listing for your game the app generates a QR code your testers can scan to give their feedback on the mobile website.

What Next?

Now that you know how to test your game and collect feedback, it's time to start iterating on your design. Once it's ready, you might ask yourself what your end goal is for your design career.